Frontotemporal Dementia: What is frontotemporal dementia?

https://www.brain.northwestern.edu/dementia/frontal.html

There is a type of dementia called "frontotemporal" which typically affects patients at a very early age. In this type of dementia, there is no true memory loss in the early stages of the type that is seen in Alzheimer's dementia. Instead, there are changes in personality, ability to concentrate, social skills, motivation and reasoning. Because of their nature, these symptoms are often confused with psychiatric disorders. There are gradual changes in one's customary ways of behaving and responding emotionally to others. Memory, language and visual perception are usually not impaired for the first two years, yet as the disease progresses and spreads to other areas of the brain, they too may become affected. Typically, the disorder affects females more than males.

The symptoms reflect the fact that the brain degeneration is not initially widespread and settles in the parts of the brain that are important for social skills, reasoning, judgement and the ability to take initiative.

When the brains of individuals with frontal lobe dementia are studied after death, the types of microscopic abnormalities that are seen are typically of two kinds. The first type is called Non-specific focal degeneration and the second is labeled Pick's disease. Non-specific focal degeneration accounts for 80% of cases of frontal lobe dementia. It is called "non specific" because there are no abnormal particles that are identifiable-only evidence that brain cells have been eliminated. Pick's disease, which accounts for 20% of cases of frontal lobe dementia, is identified under the microscope by abnormal particles called "Pick bodies", named after the neurologist who first observed them.

Comportment, Insight, and Reasoning

Frontotemporal dementia affects the part of the brain that regulates comportment, insight and reasoning. "Comportment" is a term that refers to social behavior, insight, and "appropriateness" in different social contexts. Normal comportment involves having insight and the ability to recognize what behavior is appropriate in a particular social situation and to adapt one's behavior to the situation. For example, a funeral is a solemn event requiring certain types of behavior and decorum. Similarly, while it may be perfectly natural and acceptable to take one's shoes and socks off at home, it is probably not the thing to do while in a restaurant. Comportment also refers to the style and content of a person's language. Certain types of language are acceptable in some situations or with friends and family, and not acceptable in others.

Insight, an important aspect of comportment, has to do with the ability to "see" oneself as others do. Insight is necessary in order to determine whether one is behaving in a socially acceptable or in a reasonable manner. Insight is also necessary for the patient to recognize his/ her deficits and illness. Changes in comportment may be manifested as "personality" alterations. A generally active, involved person could become apathetic and disinterested. The opposite may also occur. A usually quiet individual may become more outgoing, boisterous and disinhibited. Personality changes can also involve increased irritability, anger and even verbal or physical outbursts toward others (usually the caregiver). Comportment is assessed by observing the patient's behavior throughout the examination and interviewing other people (family and friends) who have information about the patient's "characteristic" behavior.

Individuals with frontotemporal dementia frequently have executive function and reasoning deficits. "Reasoning" refers to mental activities that promote decision-making. Being able to categorize information and to move from one perspective of a problem to another are examples of reasoning. "Executive functions" is a term that refers to yet another group of mental activities that organize and plan the flow of behavior. A good example of executive functions is what might happen if one were driving a car, talking with the passenger and suddenly having to respond to a child running into traffic. The ability to handle all the stimulation and to quickly plan a course of action is accomplished via executive functions. Individuals with frontal lobe dementia often lack flexibility in thinking and are unable to carry a project through to completion. Failure of executive functions may increase safety risk since they may not be able to plan appropriate actions or inhibit inappropriate actions.

Symptoms of Frontotemporal Dementia:

- Impairments in social skills

- inappropriate or bizarre social behavior (e.g., eating with one's fingers in public, doing sit-ups in a public restroom, being overly familiar with strangers)

- "loosening" of normal social restraints (e.g., using obscene language or making inappropriate sexual remarks) - Change in activity level

- apathy, withdrawal, loss of interest, lack of motivation, and initiative which may appear to be depression but the patient does not experience sad feelings.

- in some instances there is an increase in purposeless activity (e.g., pacing, constant cleaning) or agitation. - Decreased Judgment

- impairments in financial decision- making (e.g., impulsive spending)

- difficulty recognizing consequences of behavior

- lack of appreciation for threats to safety (e.g., inviting strangers into home) - Changes in personal habits

- lack of concern over personal appearance

- irresponsibility

- compulsiveness (need to carry out repeated actions that are inappropriate or not relevant to the situation at hand. - Alterations in personality and mood

- increased irritability, decreased ability to tolerate frustration - Changes is one's customary emotional responsiveness

- a lack of sympathy or compassion in someone who was typically responsive to others' distress

- heightened emotionality in someone who was typically less emotionally responsive

Persons with this form of dementia may look like they have problems in almost all areas of mental function. This is because all mental activity requires attention, concentration and the ability to organize information, all of which are impaired in frontal lobe dementia. Careful testing, however, usually shows that most of the problems stem from a lack of persistence and increased inertia.

Psychosocial Issues

The psychological, social, family and financial issues that affect individuals with frontotemporal dementia are drastically different from those that affect individuals with Alzheimer's type dementia. When dementia occurs earlier in life, issues such as working, teenage children and financial stress are different from the issues dealt with by individuals who are older and most likely retired. Planning for the family's financial security and for the education of children becomes a difficult prospect when an individual is faced with a dementing illness in the prime of his/her working career. The nature of the symptoms themselves are often embarrassing to family members and there may be loss of friends and other sources of social support. Finally, most adult day programs and residential care facilities are not equipped to address the special needs of the younger patient, especially if the behavioral symptoms are difficult to manage. As more is known about the disease, more policy changes may come into effect. Some residential care and adult day programs are recognizing the needs of the younger dementia patient and are beginning to offer services to meet their needs. Before making any decisions, it is best to investigate your options.

Depending on severity, a patient with impaired comportment may not be able to manage their daily activities without supervision. They may be at risk for harming themselves or being victimized because they would not be able to recognize their limitations or use proper judgement. Driving is usually unsafe for persons with this diagnosis.

Fortunately, there are steps that can be taken to provide a secure environment for the diagnosed person and obtain help for family:

- Obtain a psychiatric evaluation from an individual with experience treating people with dementia. Certain medications can help with behavior problems such as agitation and hostility.

- Share information with family and friends. This will help them better understand the patient's behavior and provide an opportunity for them to offer the diagnosed persona and their family some support and respite.

- Encourage the person to attend an early stage support group. Even if the support group is geared toward the person with early Alzheimer's disease, much information will also be relevant to Frontal Lobe Dementia.

- Meet with an attorney or financial consultant. Make sure Durable Power of Attorney forms have been completed for both health care and finances. Give copies to your doctor. An "elderlaw" attorney who is well-versed in these issues is still an appropriate choice to help you draft these documents or you may obtain the forms at many stationary stores and complete them on your own.

- Attend a caregiver support group. Listening to others who are going through similar experiences can be very comforting. They may also aid you in developing new caregiver techniques and learn about different resources within your community.

- Try to remain physically and mentally healthy. Be sure to get regular health check-ups for both the diagnosed person and family. Exercise and eat nutritious meals. Build in time for things that allow you to rejuvenate.

- Obtain a driving evaluation: Contact your local Alzheimer's Association for the driving evaluation program near you.

Frontotemporal Dementia

What is frontotemporal dementia?

There is a type of dementia called "frontotemporal" which typically affects patients at a very early age. In this type of dementia, there is no true memory loss in the early stages of the type that is seen in Alzheimer's dementia. Instead, there are changes in personality, ability to concentrate, social skills, motivation and reasoning. Because of their nature, these symptoms are often confused with psychiatric disorders. There are gradual changes in one's customary ways of behaving and responding emotionally to others. Memory, language and visual perception are usually not impaired for the first two years, yet as the disease progresses and spreads to other areas of the brain, they too may become affected. Typically, the disorder affects females more than males.

The symptoms reflect the fact that the brain degeneration is not initially widespread and settles in the parts of the brain that are important for social skills, reasoning, judgement and the ability to take initiative.

When the brains of individuals with frontal lobe dementia are studied after death, the types of microscopic abnormalities that are seen are typically of two kinds. The first type is called Non-specific focal degeneration and the second is labeled Pick's disease. Non-specific focal degeneration accounts for 80% of cases of frontal lobe dementia. It is called "non specific" because there are no abnormal particles that are identifiable-only evidence that brain cells have been eliminated. Pick's disease, which accounts for 20% of cases of frontal lobe dementia, is identified under the microscope by abnormal particles called "Pick bodies", named after the neurologist who first observed them.

Comportment, Insight, and Reasoning

Frontotemporal dementia affects the part of the brain that regulates comportment, insight and reasoning. "Comportment" is a term that refers to social behavior, insight, and "appropriateness" in different social contexts. Normal comportment involves having insight and the ability to recognize what behavior is appropriate in a particular social situation and to adapt one's behavior to the situation. For example, a funeral is a solemn event requiring certain types of behavior and decorum. Similarly, while it may be perfectly natural and acceptable to take one's shoes and socks off at home, it is probably not the thing to do while in a restaurant. Comportment also refers to the style and content of a person's language. Certain types of language are acceptable in some situations or with friends and family, and not acceptable in others.

Insight, an important aspect of comportment, has to do with the ability to "see" oneself as others do. Insight is necessary in order to determine whether one is behaving in a socially acceptable or in a reasonable manner. Insight is also necessary for the patient to recognize his/ her deficits and illness. Changes in comportment may be manifested as "personality" alterations. A generally active, involved person could become apathetic and disinterested. The opposite may also occur. A usually quiet individual may become more outgoing, boisterous and disinhibited. Personality changes can also involve increased irritability, anger and even verbal or physical outbursts toward others (usually the caregiver). Comportment is assessed by observing the patient's behavior throughout the examination and interviewing other people (family and friends) who have information about the patient's "characteristic" behavior.

Individuals with frontotemporal dementia frequently have executive function and reasoning deficits. "Reasoning" refers to mental activities that promote decision-making. Being able to categorize information and to move from one perspective of a problem to another are examples of reasoning. "Executive functions" is a term that refers to yet another group of mental activities that organize and plan the flow of behavior. A good example of executive functions is what might happen if one were driving a car, talking with the passenger and suddenly having to respond to a child running into traffic. The ability to handle all the stimulation and to quickly plan a course of action is accomplished via executive functions. Individuals with frontal lobe dementia often lack flexibility in thinking and are unable to carry a project through to completion. Failure of executive functions may increase safety risk since they may not be able to plan appropriate actions or inhibit inappropriate actions.

Symptoms of Frontotemporal Dementia:

- Impairments in social skills

- inappropriate or bizarre social behavior (e.g., eating with one's fingers in public, doing sit-ups in a public restroom, being overly familiar with strangers)

- "loosening" of normal social restraints (e.g., using obscene language or making inappropriate sexual remarks) - Change in activity level

- apathy, withdrawal, loss of interest, lack of motivation, and initiative which may appear to be depression but the patient does not experience sad feelings.

- in some instances there is an increase in purposeless activity (e.g., pacing, constant cleaning) or agitation. - Decreased Judgment

- impairments in financial decision- making (e.g., impulsive spending)

- difficulty recognizing consequences of behavior

- lack of appreciation for threats to safety (e.g., inviting strangers into home) - Changes in personal habits

- lack of concern over personal appearance

- irresponsibility

- compulsiveness (need to carry out repeated actions that are inappropriate or not relevant to the situation at hand. - Alterations in personality and mood

- increased irritability, decreased ability to tolerate frustration - Changes is one's customary emotional responsiveness

- a lack of sympathy or compassion in someone who was typically responsive to others' distress

- heightened emotionality in someone who was typically less emotionally responsive

Persons with this form of dementia may look like they have problems in almost all areas of mental function. This is because all mental activity requires attention, concentration and the ability to organize information, all of which are impaired in frontal lobe dementia. Careful testing, however, usually shows that most of the problems stem from a lack of persistence and increased inertia.

Psychosocial Issues

The psychological, social, family and financial issues that affect individuals with frontotemporal dementia are drastically different from those that affect individuals with Alzheimer's type dementia. When dementia occurs earlier in life, issues such as working, teenage children and financial stress are different from the issues dealt with by individuals who are older and most likely retired. Planning for the family's financial security and for the education of children becomes a difficult prospect when an individual is faced with a dementing illness in the prime of his/her working career. The nature of the symptoms themselves are often embarrassing to family members and there may be loss of friends and other sources of social support. Finally, most adult day programs and residential care facilities are not equipped to address the special needs of the younger patient, especially if the behavioral symptoms are difficult to manage. As more is known about the disease, more policy changes may come into effect. Some residential care and adult day programs are recognizing the needs of the younger dementia patient and are beginning to offer services to meet their needs. Before making any decisions, it is best to investigate your options.

Depending on severity, a patient with impaired comportment may not be able to manage their daily activities without supervision. They may be at risk for harming themselves or being victimized because they would not be able to recognize their limitations or use proper judgement. Driving is usually unsafe for persons with this diagnosis.

Fortunately, there are steps that can be taken to provide a secure environment for the diagnosed person and obtain help for family:

- Obtain a psychiatric evaluation from an individual with experience treating people with dementia. Certain medications can help with behavior problems such as agitation and hostility.

- Share information with family and friends. This will help them better understand the patient's behavior and provide an opportunity for them to offer the diagnosed persona and their family some support and respite.

- Encourage the person to attend an early stage support group. Even if the support group is geared toward the person with early Alzheimer's disease, much information will also be relevant to Frontal Lobe Dementia.

- Meet with an attorney or financial consultant. Make sure Durable Power of Attorney forms have been completed for both health care and finances. Give copies to your doctor. An "elderlaw" attorney who is well-versed in these issues is still an appropriate choice to help you draft these documents or you may obtain the forms at many stationary stores and complete them on your own.

- Attend a caregiver support group. Listening to others who are going through similar experiences can be very comforting. They may also aid you in developing new caregiver techniques and learn about different resources within your community.

- Try to remain physically and mentally healthy. Be sure to get regular health check-ups for both the diagnosed person and family. Exercise and eat nutritious meals. Build in time for things that allow you to rejuvenate.

- Obtain a driving evaluation: Contact your local Alzheimer's Association for the driving evaluation program near you.

A Lesser-Known Dementia That Steals Personality

It was the annual Labor Day tradition for the Savini family, a makeshift version of The Gong Show performed before the neighborhood on a wooden deck stage at their beach house in Massachusetts. In past years, Nicole Savini’s mom and friends dressed up in nightgowns as the housewives version of The Supremes, singing “Stop in the Name of Love” into wooden spoons.

The theme this year involved a tongue-in-cheek skit on global warming, with the family singing rewritten lyrics to “Don’t Worry Be Happy,” complete with a fake weathercast warning of Sharknado’s arrival, as well as the Lobster-pocolypse and Clamageddon. Nicole’s dad, John, dressed up as a shark from Jamaica.

But one person was emotionally absent from the production, though physically present: Nicole’s mom, Kathy.

For most of Nicole’s life, her mother would get into the spirit of “The Gong Show,” dressing up in costume, practising the choreography and lines. Instead, this year a special seat had been reserved for her among the lawn chairs in the audience, and while everyone else cracked up, Kathy didn’t react.

It took many months, and some Internet research, for the family to get a diagnosis. Her mother’s change in behavior was caused by a little-known disease called frontotemporal dementia, a neurological disorder centered in the frontal lobe of the brain, the part responsible for our behavior and emotions. While Alzheimer’s usually affects older people, and is detected as a person begins to lose memory, frontotemporal dementia causes people to lose their personalities first, and usually hits in the prime of their lives — the 30s, 40s, and 50s.

Over the last decade, new research in patients with frontotemporal dementia and other illnesses, has helped neuroscientists understand more about the roles different parts of the brain play in where our personalities come from.

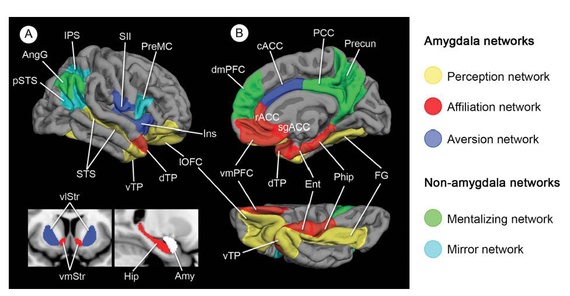

A study released in October by Dr. Brad Dickerson and colleagues at Harvard Medical School in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatrypinpointed regions in the brain that showed atrophy from frontotemporal dementia and found that those with the most damage to the “perception network” (amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, superior temporal, and fusiform cortex) also showed the most prominent difficulty responding to social cues, facial expressions, and eye gaze, and had the most trouble interpreting gestures and body language—the kind of cues that sarcasm relies on.

Frontotemporal dementia patients with the greatest deterioration in the “affiliation network,” (involved in motivating a person to connect with others and generating rewarding feelings during social interactions) exhibited the most severe social and emotional detachment, and patients with the greatest damage to the “aversion network” (involved in detecting and avoiding untrustworthy or threatening individuals) became more willing to trust strangers, and in some cases gave away private personal information despite negative consequences.

On the surface people with frontotemporal dementia might still seem normal, able to hold a job, and talk to people about the weather. But those traits that family and friends know and love—such as empathy, shyness, shame, pride, or wittiness—begin to disappear.

As the disease invades parts of the brain, patients’ altered behaviors have helped researchers understand how embarrassment comes from the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex. Or how recognizing sarcasm can be traced to structures in the temporal lobes, according to UC San Francisco researcher Kate Rankin, who has studied frontotemporal dementia patients.

Nicole’s mom’s diagnosis was especially ironic, given their close-knit, funny family in Marshfield, Massachusetts. Sarcasm had always been a central element of Nicole’s life, leading her to produce satirical segments for Stephen Colbert’s show, like this one on Maine’s missing scallop gonads, which, today, would go right over her mom’s head.

There are moments now when all Nicole can do is laugh at how simultaneously tragic and hilarious her mother’s illness is. She sees absurdity in situations that her mother can no longer grasp. Lately, Kathy has been obsessed with opening people’s mailboxes. “We keep telling her it’s a federal offense,” said Nicole.

Then, Kathy will open another.

“Mom what is that?”

“Federal offense,” she will reply in a monotone. “Federal offense.”

“People say all the time that comedy comes from tragedy,” Nicole said. “If you can’t laugh, you’re just going to be crying all the time. But it’s an overwhelming disease. You are really helpless. There is no medication, no road map, no end in sight.”

* * *

An estimated 50,000 to 60,000 people in the U.S. are diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, although experts estimate that many more suffer from the condition but have not yet received a correct diagnosis, according to The Association for Frontotemporal Dementias.

The symptoms are often wrongly blamed on alcoholism, depression, menopause, mid-life crises, stress, or schizophrenia, and patients can go through years of negative tests for other ailments like cancer, strokes, and syphilis before learning the truth about what is actually wrong. People living with frontotemporal dementia, are unaware that they have even changed. But for loved ones, sometimes it’s like living with a stranger.

It affects each patient’s character differently. A proud CEO and dedicated father could one day start walking around with his pants down, or stealing candy from a convenience store without embarrassment or shame. A devoted girlfriend might nonchalantly tell her partner intricate details of past relationships with other men.

Nurse and medical anthropologist Jill Shapira, who works at the University of California, Los Angeles with frontotemporal dementia patients and their families, recounted the story of a husband who had always been loving and kind. One day, his wife fell on the floor. As she was sprawled on her back, he stood over her and asked, “When’s dinner?”

“That’s often a wake up call,” Shapira said. Spouses tend to think their partner is having an affair, or has lost interest in them. “First you get pissed. Then you say this isn’t him. This isn’t the person I married.”

* * *

Kathy fell in love with John, when they were teens, after he wooed her while playing a comedic role in a high school play, “The Perfect Idiot.”

“I was the star, but I was not the idiot,” Nicole’s dad told her recently, when she asked about their love story. Nicole’s mother had told her that she fell in love with John because “he was such a ham.”

“I don’t remember her saying I was a ham,” John replied. “I think she might have said she was impressed by my talent. I don’t remember the word ham coming up, just talented maybe.”

When prom came around, John wasn’t going to ask Kathy. He planned on asking another girl, because he had asked Kathy out once before in 9th grade, and she said no. She had to work. But after he impressed her with the play, Kathy told him she needed a date. “She decided I was going to ask her,” he said. “I was Project Prom.” After they ended up dating, he asked her about the 9th grade rejection. Kathy said very matter-of-factly that she did, indeed, have to work that day.

Growing up, Nicole’s dad was the biggest joker of all.

mom (left to right) (Courtesy Nicole Savini)

He would spend months making up lyrics and skits for “The Gong Show,” which has involved various family members and neighbors dressed as cowboys, Vegas showgirls, or news reporters in ponchos caught in Hurricane Earl, replacing the lyrics to “My Girl,” with them singing, “My Earl.” One year, Nicole’s dad dressed up a rapper, “L.L. Bean.”

One of the first telltale signs of Kathy’s illness was the weight gain. She shoved food into her mouth without restraint. Once, as Nicole prepared a birthday cake with M&Ms, her mom reached in to grab a handful.

“Don’t, they’re for the cake,” Nicole told her.

“Okay,” her mom replied, and then put them in her mouth anyway.

It was clear to Nicole then, her mom clearly had lost control of her behavior. She also became apathetic, and had trouble organizing her shelves or keeping appointments. She gained 100 pounds in a year.

At first, doctors thought it could be sleep apnea. But Nicole’s sister, Catherine, didn’t buy it. “I got kind of pushy with the neurologist,” Catherine said. “I made my mother go back to make another appointment, even though she didn’t want to…I remember crying to my mother, saying, ‘I just think something is wrong and I think you need to go.”

Rankin of UCSF, has conducted tests on patients with frontotemporal dementia and other brain diseases, putting subjects through video tests featuring actors who recite lines in a sitcom style like, “No of course you don’t look fat,” (when he does), or “I’d be happy to do it. I’ve got plenty of time.” (when he doesn’t). The patients had to observe facial expressions, voice patterns, gestures, and posture, to determine the speaker’s intended meaning, from cues like eye rolling and exaggerated voice prosody, and then answer questions about their sincerity or sarcasm.

Rankin’s and others’ research has shown that the underlying neurological layers of sarcasm involve regions of the superior frontal gyrus, which is involved in self-awareness, decision making, and laughter, as well as the medial and anterior temporal lobes, which have been indicated in language processing and integrating information about attitudes, intentions, and emotions. Understanding more complex forms of sarcasm can also require parts of the brain involved in empathy and reading other people’s mental states.

Other scientists have found that 70 percent of frontotemporal dementia patients showed damage to brain cells called von Economo neurons, found in the anterior cingulated cortexes, which are involved in self-awareness and socializing.

“Studies like these shed light on the ways that specific social skills are hardwired into our brains to a greater extent than people previously would have believed,” said Rankin, “which is why a disease like frontotemporal dementia can make someone act like a completely different person.”

Dr. Bruce Miller, who heads the University of California, San Francisco Memory and Aging Center, believes these discoveries in the brains of frontotemporal dementia patients will also one day influence how psychiatric disorders are treated, like depression, bipolar disorder, or ADHD. “If you don’t develop these fine-grained assessments of emotional deficits in psychiatric patients, you’ll never understand them.” Brain research is important for frontotemporal dementia patients. “It’s even more exciting for the psychiatric diseases, which are more common.”

“Oh, hon, I didn’t realize you were so hungry,” John joked.

Everyone was surprised that Kathy laughed.

Another time, Nicole tried to get her mom to put on her pants by singing the hokey pokey. Her mom cracked a smile.

“I see her wake up, it’s almost like I can see the neuro-whatever-you-call-thems firing in her brain,” Nicole wrote in an essay. “She’s back and she’s with me. And, for a moment, I am with my old mom, the one with a sharp wit, who can clearly see that, frankly, I look ridiculous.”

Occasionally, Kathy still made jokes. Once, she wore a fake leopard skin coat and announced, “No animals were harmed in the making of this coat.” She went out to dinner and with her daughters, who ordered mussels. Kathy said, “I don’t like mussels unless they’re on dad.”

Kathy’s deterioration took longer for John to accept. At first, he continued going on vacations with her, as if life was normal. They went to Niagara Falls, and John made an appointment for Kathy at the spa, while he went golfing. Kathy went for a walk instead, stopping at an ice cream cart, where she started to eat without paying the vendor, who got so upset he called the police.

When officers arrived, Kathy told them, “Well, I don’t have $4. Are you going to arrest me for eating ice cream?”

The next day John tracked down the ice cream man to give him the $4. That was when he learned he could no longer leave her alone.

Another day, Nicole and her dad opened the door on Kathy and saw that in an attempt to wash her face, she had actually covered her arms and face with shaving cream. Nicole and John burst out laughing. They looked at each other for approval like, “Can we laugh about this or not?”

Humor has helped guide Nicole and her family through the challenges of dealing with her mother’s personality changes. In the beginning, John told Kathy, “We’ve laughed every day up to this point, so why don’t we just laugh our way through the rest of the way?”

In New York, Nicole joined a support group for families whose loved ones have the disease. As soon as Nicole arrived, she said, “Just so everyone knows, I’m not interested in being here.”

At one point, the social worker asked everyone to say something unexpectedly good about what had happened since the diagnosis. When her turn came, Nicole said, “There’s nothing. I’m not going to make something up. I don’t think there’s a thing.”

Her family was no longer the same. She used to look forward to going home, and now it only made her stressed out. Her old mom was gone.

Other people were more positive. They talked about their families becoming closer, about recognizing what most others take for granted, and of learning to take care of themselves first, even before sacrificing for their loved ones.

Bullshit, Nicole thought.

But she kept attending the meetings, making friends with people like Deanna Angello, whose father also suffered from frontotemporal dementia. Together, they commiserated. Deanna’s father had been a music aficionado, with a vast collection, but he lost interest in listening to his albums. He was also a huge fan of “Seinfeld.” At every chance he could, Deanna’s father would go into the minute details of the last episode he saw, referring to George, Kramer, Elaine, and Jerry like old friends.

“He could recite any episode ever made,” Deanna said.

One day, about nine months after the diagnosis, Deanna went home and noticed that he had lost interest in “Seinfeld” too. He didn’t find the show funny anymore and would stare apathetically at cartoons, never changing the channel.

“How do you move forward with your life?” Deanna would say to Nicole. They would talk about feeling guilt for living their own lives, when their parents’ lives seemed to be withering away.

Nicole took a month off work to help care for her mother. “I went into Stephen’s office and started crying.” Colbert hugged her and said, “Calm down, whatever it is.” When Nicole went home, she realized her mother was losing her ability to carry on a conversation.

The prognosis only seemed to get darker. The Savinis learned that frontotemproal dementia can be passed down hereditarily. Nicole found out that there was a chance she may have inherited the protein that causes it. But she refuses to take the test to determine whether or not that could actually be the case. She does not want to know. Neither does her sister.

Five years after the diagnosis, Kathy doesn’t make jokes or laugh at them anymore, not even in a knee-jerk reaction kind of way.

“But there are moments,” Nicole said. “They are fewer and farther between, but sometimes they still exist. They come out even when you think all is lost.”

Something about Kathy’s grandson brings out a softer side. Kathy no longer hugs her adult daughters, Nicole said. But she lets her grandson sit on her lap. He smiles at her. And every once in a while, she smiles back.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

A Lesser Known Dementia that Steals Personality

Click Here

Frontal lobe dysfunction explains some behaviors, doctors told

As endearing as some of the behaviors may seem to outsiders, the symptoms of "frontal lobe dysfunction" often bring caregivers to tears.

Frontal lobe dysfunction, or executive dysfunction syndrome -- EDS -- or "vulnerable brain," or "Pick's disease" causes changes in personality and behaviour and erases inhibitions. Victims make poor decisions and do not anticipate the consequences of their sometimes strange, socially unacceptable actions. "If it feels good, do it," is typical of a victim of frontal lobe dysfunction, Dr. Steven Wengel told a group of McCook doctors when he and Dr. Carl Greiner, of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, stopped in McCook Nov. 8.

"This is not Alzheimer's disease," Dr. Wengel said. Victims' cognition and memory are good, he said; they know what they've done -- they remember doing it. They just don't know it's inappropriate, or that they have frontal lobe dysfunction.

The syndrome has been around for years, Dr. Wengel said, telling the tale of Phineas Gage, not an old gentleman, who in the 1840s, suffered frontal lobe damage when a three-foot-long iron rod was blown through his head. Amazingly, he recovered from that accident, but within weeks he became uncharacteristically obstinate, sexually inappropriate and childlike. Records indicate "he just wasn't himself," Dr. Wengel said. Phineas Gage was unable to hold a job due to his socially-inappropriate behaviour, and died 11 years later.

"A patient with executive dysfunction generally does not know that he has it," Dr. Wengel said. "No one ever comes to me and says, 'I think I have bad judgement. Help me with this'."

"We're seeing this now in victims of car accidents and skateboard accidents," Dr. Wengel said, and in soldiers suffering closed-head brain trauma caused by explosions and bombings.

New Mexico Senator Pete Domenici recently announced he will not seek re-election because of this degenerative brain disease.

Normal development of the brain's executive function is a gradual process starting in the pre-teen years through the 20s (" ... or never," Dr. Wengel said. "Not everyone gets here.")

Good frontal lobe function is evidenced by the ability to make decisions, many unconsciously. Even subtle impairment will show in poor decision-making skills and a lack of awareness of consequences.

Abnormal frontal lobe function manifests itself slowly, and early on with a loss of personal and social awareness, insight and disinhibition.

Typical behavioural problems include:

* Socially inappropriate behaviour, such as making tactless comments, sexually inappropriate jokes, comments, suggestions and/or requests;

* Aggressive behaviour, (for example, becoming easily angered while driving);

* Hoarding; and

* Shoplifting.

Physical signs will include:

* Early, primitive reflexes and incontinence; and

* Late, akinesia (absence or disturbance of motion in a muscle); rigidity; tremor; or low blood pressure.

Treatment includes, "Structure, structure, structure," Dr. Wengel said. "Structure their world, and educate their family." Dr. Wengel recommends setting aside adequate time for tasks and giving concrete, written instructions.

Some medications will help with apathy and with repetitive behaviour such as gambling, touching and inappropriate sexual behaviour, he said. "Disinhibition doesn't change. That's tough."

"This isn't Alzheimer's," he said, "But Alzheimer's (support) groups can be helpful."

"We can't bring back good frontal lobe function. We can't fix it," Dr. Wengel said. "We can help the family cope."

Dr. Carl Greiner MD, a UNMC professor of psychiatry, practices adult and forensic psychiatry and deals with issues of cognitive impairment and how it can result in legal problems.

Dr. Greiner studies psychiatry and the law, asking, "Is someone with EDS (executive dysfunction syndrome) culpable?"

EDS is hard to recognise, Dr. Greiner said. Victims are, "mentally rigid. The lights are on, but nobody's home. They seem OK, but they're not."

"Victims can get into trouble," he explained, "because their concept of 'the right time and place' is disrupted."

Everyone has a bit of executive dysfunction, Dr. Greiner said, explaining that phonics in the third grade made absolutely no sense to him. But, someone who has had good executive brain function and is now losing it will not function as well as in the past, he said.

"You don't seem like yourself," may be the comment made to an EDS sufferer, Dr. Greiner said.

Someone with EDS is a risk to him/herself, becoming easily befuddled by simple tasks -- such as tripping because they've forgotten to lift their feet to walk up a flight of stairs, or getting burned by forgetting the process of pouring hot coffee, Dr. Greiner said.

The risk is conveyed to others when someone with EDS insists on driving.

Someone with EDS can easily become a victim to predatory practices, Dr. Greiner said. "Attorneys and families can do a lot to reduce harm with good risk management," Dr. Greiner said. "Attorneys and families need to understand EDS to protect the physical, social and financial status of a victim."

"Money, meds and driving" are the three biggest challenges for families dealing with victims of EDS, Dr. Wengel said.

"Early on, symptoms of EDS are illusive ... they're tough to pin down," he said. There is a battery of paper-and-pencil tests that a suspected victim can be put through, including being asked to draw the face of a clock. Planning ahead to fit 12 items equidistance within a circle is a function of good frontal lobe function, he said. An EDS victim often bunches all the numbers together or only makes it half-way around before he/she runs out of numbers. One victim actually drew facial features on a clock, Dr. Wengel said.

Approaching a victim about an EDS diagnosis requires diplomacy, Dr. Wengel said. Oftentimes, a sufferer denies anything is wrong, and will seek the advice of another doctor.

Dr. Greiner said he gently suggests, "You may have an illness ... you may be having small strokes." It's not a case of having to tell someone something repeatedly before he/she understands it. The information, "is just not being integrated," Dr. Greiner said.

He said, "It's not about 'being crazy.' It's about trying to find an illness."

Dr. Wengel said there is at times an overlap between short-term memory loss and frontal lobe disfunction. "On any given day, any one of us can have some degree of frontal lobe dysfunction," he said.

"Frontal lobe dysfunction is a real challenging syndrome to pin down," he said.

A press release from Jo Giles, communications specialist in the Department of Public Affairs, UNMC, indicates:

Frontal lobe dysfunction can occur when the frontal lobes are damaged, such as in a head injury, or in people who are elderly and in the early stages of dementia, or those who suffer from more severe mental disorders, like schizophrenia.

Symptoms include socially inappropriate behavior, financial indiscretions or impaired driving, or a reduction in the ability to solve problems.

Dr. Greiner said people with "vulnerable brains" are more likely to make poor decisions and can be more easily deceived.

"Frontal lobe dysfunction is common, but not well understood. We're interested in sharing how to recognize cognitive impairment early so that the patient gets the necessary health care he or she needs, and to protect them from undue influence and avoid accidents and falls," Dr. Greiner said.

"This is part of our commitment to provide information on important mental health care issues," he said.

Dr. Wengel, chairman of the UNMC Department of Psychiatry, is dedicated to all levels of education. Since 1994, Dr. Wengel has been a consultant for geriatric cases at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Omaha. He received his medical degree from UNMC in 1986, then remained to complete a residency in psychiatry in 1990 and a fellowship in geropsychiatry in 1991. Dr. Wengel's research focuses on geriatric mental health issues, such as Alzheimer's disease, anxiety disorders and depression.

Dr. Greiner received his medical degree from the University of Cincinnati where he did his psychiatry residency. He is board certified in psychiatry and neurology with special qualifications in forensic psychiatry. He practices adult and forensic psychiatry, which deals with issues of cognitive impairment and how that can result in legal problems.

UNMC is the only public health science center in Nebraska. Its educational programs are responsible for training more health professionals practicing in Nebraska than any other institution.

Through its commitment to education, research, patient care and outreach, UNMC and its hospital partner, the Nebraska Medical Center, have established themselves as one of the country's leading centers in cancer, transplantation biology, bioterrorism preparedness, neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, genetics, biomedical technology and ophthalmology.

UNMCs research funding from external sources now exceeds $80 million annually and has resulted in the creation of more than 2,400 highly skilled jobs in the state.

UNMC's physician practice group, UNMC Physicians, includes 513 physicians in 50 specialties and subspecialties who practice primarily in The Nebraska Medical Center.

For more information, go to UNMC's Web site at www.unmc.edu.

Direct Article

Click Here

Study shows why some dementia patients lack empathy

He would stare at people until they squirmed, place his hands on the backs of men he did not know and once pointed and laughed at a paraplegic.

Gordon James had developed early-onset dementia, a disease characterised by a lack of empathy, confusion, inappropriate behaviour and, in his rare form of the disease, loss of speech.

"The way that I would normally show affection to him didn't mean that much to him any more," Mrs James said. "He would walk away or push your hand away. It's a very, very cruel disease."

Patients with Alzheimer's disease generally remain warm and engaged despite their cognitive decline, but those with the behavioural-variant of frontotemporal dementia [bvFTD] undergo a jarring change in personality.

These early-onset dementia patients have blunted emotions and become puzzled by affection, uninterested in socialising and less responsive to the feelings of others.

But a study published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease may give comfort to carers who have borne the brunt of these changes. It indicates that the changes result from fading grey matter in the region of the brain that governs empathy.

Researchers from Neuroscience Research Australia investigated 71 individuals including 25 with Alzheimer's, 24 with bvFTD and 22 healthy older control participants through cognitive assessments, carer interviews and neuroimaging.

Both the experimental groups had reduced capacity to understand and appreciate the emotions of others, known as cognitive empathy. But the bvFTD patients were significantly more impaired when it came to sharing the emotions and emotional experiences of others – or affective empathy.

The impairment in cognitive empathy among the Alzheimer's group was found to be a consequence of their overall cognitive decline, rather than an impairment in empathy per se.

So while they found it difficult to explain how a book character might be feeling, they were still likely to become upset if they saw somebody crying in the street.

But among the bvFTD patients, the loss of empathy was related to patchy grey matter in the frontoinsular cortices of the brain, the integrity of which is critical to social functioning.

Lead author Muireann Irish said this explained why Alzheimer's patients continued to be socially appropriate in spite of the decline in cognitive function.

"There isn't the change in personality, which I think is one of the most jarring things about frontotemporal dementia patients," Dr Irish said.

"[This study] gives more knowledge and insight to the caregivers that there's an organic reason for this change that becomes so distressing.

"Empathy is an abstract concept in a way. It's not as easily quantified as memory loss or changes in language and it can be seen as a personality issue or somebody being deliberately unsympathetic, but this shows there's a region in the brain that changes."

Mrs James said she had to learn to adjust to the new ways of her husband, who is now living in care.

"He couldn't change, but I could, so I had to re-train my brain and re-train myself to cope with it," Mrs James said.

For Louise Palmer, the descent into dementia was fast.

Diagnosed at the age of 53, she was put into full-time care three years later, during which time her three children had to learn to adjust to her new personality.

"A lot of her emotions are blunted," daughter Riley Palmer said.

"She's a lot more anxious and she's a lot more angry, but her ability to connect with other people's lives is much less.

"My sister got engaged last year and she was really excited to tell all of us, but when she told Mum, Mum didn't even look at her.

"Then 30 seconds later Mum looked at her and said, 'Can you help me'?"

Why Some Dementia Patients Lack Empathy

Click Here

The FTD Toolkit

Click Here