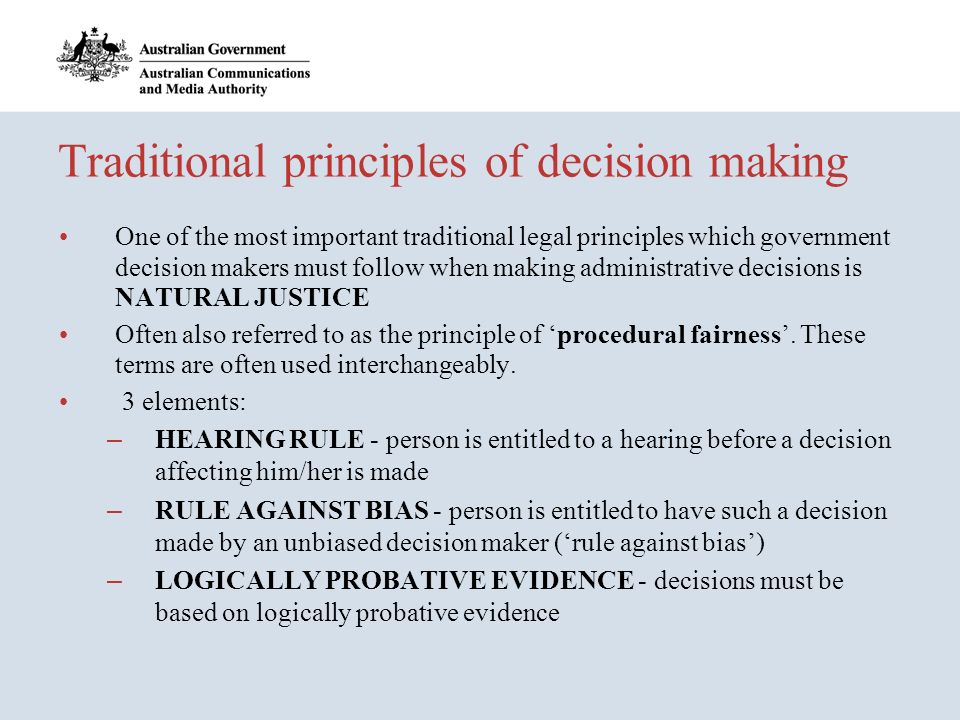

Natural Justice is the :

- The right to be heard, to have your say and to answer accusations;

- The right to be judged in an impartial manner and by an impartial officer;

- The right to submit facts and evidence.

The issue in the Tribunal system is that Members have the right to 'determine' matters as they 'see fit' and to ignore the rules of evidence. That's right IGNORE evidence. And Appeals are limited to Questions of Law(not facts).

(This does not happen in a Court)

These two issues have lead to many calling the Tribunals system as despotic and open to abuse of power and corruption. The ultimate result comes down to the Member. Yes many Members may not abuse their powers, but the SYSTEM is open to such abuse and, as we have seen, many verdicts have ignored vital evidence to the distress of victims and families.

Below are some articles on Procedural Fairness and Natural Justice. Just keep in mind, evidence can and is often ignored. And this is why we view the Guardianship System and Unfair and dangerous in its current form, favouring State Governments who gain from the decisions.

What is Procedural Fairness?

What is procedural fairness?

The common law has recognised, a duty to accord a person procedural fairness (also known as "natural justice") when making a decision that affects their rights, interests or legitimate expectations, at least in certain circumstances. The duty only arises if the decision affects a person individually rather than as a member of the public or a class of the public. Also, the duty may be removed by the clear manifestation of a contrary statutory intention.

Breach of a similar duty is a ground for judicial review under the Administrative Decision (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) and State and Territory legislation (in this article we'll be looking at the application of the common law duty in private contexts, outside of the realm of traditional judicial review).

The duty to accord procedural fairness consists of three key rules:

-

the hearing rule, which requires a decision-maker to accord a person who may be adversely affected by a decision an opportunity to present his or her case;

-

the rule against bias, which requires a decision-maker not to have an interest in the matter to be decided and not to appear to bring a prejudiced mind to the matter; and

-

the "no evidence" rule, which requires a decision to be based upon logically probative evidence.

The precise requirements of procedural fairness will depend on the circumstances of each case, including the nature of the inquiry, the subject-matter being dealt with and the rules under which the private body is acting.

VCAT’S NATURAL JUSTICE OBLIGATIONS

By Justice Emilios Kyrou, Supreme Court of Victoria Paper delivered at the VCAT on 23 June 2010

Ombudsman Western Australia GUIDELINES Procedural fairness (Natural Justice)

Serving Parliament - Serving Western Australians

Revised May 2009

What is procedural fairness?

Procedural fairness is concerned with the procedures used by a decision-maker, rather than the actual outcome reached. It requires a fair and proper procedure be used when making a decision. The Ombudsman considers it highly likely that a decision-maker who follows a fair procedure will reach a fair and correct decision.

Is there a difference between natural justice and procedural fairness?

The term procedural fairness is thought to be preferable when talking about administrative decision-making because the term natural justice is associated with procedures used by courts of law. However, the terms have similar meaning and are commonly used interchangeably. For consistency, the term procedural fairness is used in this fact sheet.

Does procedural fairness apply to every government decision?

No. The rules of procedural fairness do not need to be followed in all government decision-making. They mainly apply to decisions that negatively affect an existing interest of a person or corporation. For instance, procedural fairness would apply to a decision to cancel a licence or benefit; to discipline an employee; to impose a penalty; or to publish a report that damages a person’s reputation.

Procedural fairness also applies where a person has a legitimate expectation (for example, continuing to receive a benefit such as a travel concession). Procedural fairness protects legitimate expectations as well as legal rights. It is less likely to apply to routine administration and policy-making, or to decisions that initially give a benefit (for example, issuing a licence in the first instance).

In some rare circumstances, the requirement to provide procedural fairness is specifically excluded by Acts of Parliament (for example, section 115 of the Sentence Administration Act 2003).

The rules of procedural fairness require:

• a hearing appropriate to the circumstances;

• lack of bias;

• evidence to support a decision; and

• inquiry into matters in dispute.

What is “the hearing rule”?

A critical part of procedural fairness is ‘the hearing rule’. Fairness demands that a person be told the case to be met and given the chance to reply before a government agency makes a decision that negatively affects a right, an existing interest a legitimate expectation which they hold. Put simply, hearing the other side of the story is critical to good decision-making.

In line with procedural fairness, the person concerned has a right:

• to an opportunity to reply in a way that is appropriate for the circumstances;

• for their reply to be received and considered before the decision is made;

• to receive all relevant information before preparing their reply. The case to be met must include a description of the possible decision, the criteria for making that decision and information on which any such decision would be based. It is most important that any negative information the agency has about the person is disclosed to that person. A summary of the information is sufficient; original documents and the identity of confidential sources do not have to be provided;

• to a reasonable chance to consider their position and reply. However, what is reasonable can vary according to the complexity of the issue, whether an urgent decision is essential or any other relevant matter; and

• to genuine consideration of any submission. The decision-maker needs to be fully aware of everything written or said by the person, and give proper and genuine consideration to that person’s case.

How does procedural fairness apply to an individual who may be negatively affected by a government decision?

If you are going to be negatively affected by a government decision, you are entitled to expect that the decision maker will follow the rules of procedural fairness before reaching a conclusion. In particular, you are entitled to:

Be told the case to be met (for example, that an agency is considering withdrawing an existing entitlement or benefit such as a rebate or an allowance), including reasons for this proposal and any negative or prejudicial information relating to you that is to be used in the decision-making process.

The case to be met could be a letter or a draft report, or it could be a summary of the issues being considered by the decision-maker. It is not necessary for you to receive copies of all original documents or the identity of confidential sources be revealed.

A real chance to reply to the case to be met, whether that be in writing or orally. The type of hearing should be proportional to the nature of the decision. For instance, if the consequences of the proposed decision are highly significant, a formal hearing process may be warranted. In contrast, if the matter is relatively straightforward, a simple exchange of letters may be all that is needed. Generally, in any oral (or face-to-face) hearing, it is reasonable to bring a friend or lawyer as an observer, so you may wish to consider this.

In your reply, you may, amongst other things, wish to:

• deny the allegations;

• provide evidence you believe disproves the allegations;

• explain the allegations or present an innocent explanation; and

• provide details of any special circumstances you believe should be taken into account.

You must have the chance to give your response before the decision is made, but after all important information has been gathered. This is so you can be given all the information you are entitled to and be aware of the issues being considered by the decision-maker.

The decision-maker should have an open mind (be free from bias) when reading or listening to what you have to say.

How does procedural fairness apply to an investigator?

If you are investigating a matter or preparing a report for a decision-maker, it is good practice to consider the requirements of procedural fairness at every stage of your investigation.

Procedural fairness is an essential part of a professional investigation and benefits both parties. As an investigator, acting according to procedural fairness can help you by providing:

• an important means of checking facts and identifying major issues

• comments made by the subject of the complaint that can expose weaknesses in the investigation

• advance warning of areas where the investigation report may be challenged.

Depending on the circumstances, procedural fairness requires you to:

• inform those involved in the complaint of the main points of any allegations or grounds for negative comment against them. How and when this is done is up to you, depending on the circumstances

• provide people with a reasonable opportunity to put their case, whether in writing, at a hearing or otherwise. It is important to weigh all relevant circumstances for each individual case before deciding how the person should be allowed to respond to the allegations or negative comment.

• In most cases it is enough to give the person opportunity to put their case in writing. In others, however,procedural fairness requires the person to make oral representations. Your ultimate decision will often need to balance a range of considerations, including the consequences of the decision

• hear all parties to a matter and consider submissions

• make reasonable inquiries or investigations before making a decision. A decision that will negatively affect a person should not be based merely on suspicion, gossip or rumour. There must be facts or information to support all negative findings. The best way of testing the reliability or credibility of information is to disclose it to a person in advance of a decision, as required by the hearing rule

• only take into account relevant factors

• act fairly and without bias. If, in the course of a hearing, a person raises a new issue that questions or casts doubt on an issue that is central to a proper decision, it should not be ignored. Proper examination of all credible, relevant and disputed issues is important

• conduct the investigation without unnecessary delay

• ensure that a full record of the investigation has been made.

Of course, wherever there is a requirement to apply particular procedures in addition to those that ensure procedural fairness, the terms of that statutory obligation must also be followed.

The Ombudsman recommends that whenever it is proposed to make adverse comment about a person, procedural fairness should be provided to that person before the report is presented to the final decision-maker. This should be done as a matter of best practice.

There is no requirement that all the information in your possession needs to be disclosed to the person. However in rare cases, such as a serious risk to personal safety or to substantial amounts of public funds, procedural fairness requirements need to be circumvented due to overriding public interest. If you believe this exists, make sure you seek expert advice and document it.

How does procedural fairness apply to the decision-maker?

Except in rare circumstances where procedural fairness is excluded by statute, if you are making a decision which will affect the rights, interests or legitimate expectations of a person, you must comply with the rules of procedural fairness. In other words, you must ensure:

• you allow the individual a fair hearing (or verify that the individual has been granted a fair hearing) that is neither too early or too late in the decision-making process; and

• you are unbiased. This includes ensuring that from an onlooker’s perspective there is no reasonable perception of bias.

For example, personal, financial or family relationships, evidence of a closed mind or participation in another role in the decision-making process (such as accuser or judge) can all give rise to a reasonable perception of bias. If this is the case, it is best to remove yourself from the process and ensure an independent person assumes the role of decision-maker.

If you are relying on a briefing paper that summarises both sides of the case and makes a proposal, it is often a

good idea to disclose a draft of the briefing paper to the person, even though a hearing has earlier been held.